Footnotes to triangular cartographies, 2021-2020

Videos by Nina Cavalcanti

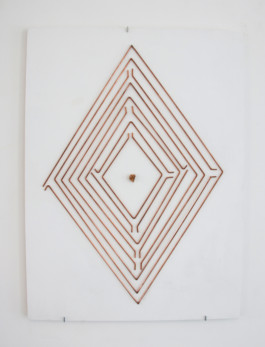

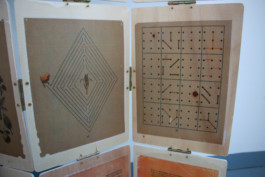

The state of living spring, 2021

Woodplate 70 x 100 cm, copper and stone.

Labyrinth made of copper and stone of the osun river, sacred forest of Osogbo, Nigeria.

Bananas to the king, 2019 - 2021

01 steel triangle; 2 casks; 2 CUC coins; 02 imperial palm seeds; 2 wooden plate photo transfers; 01 Photograph 15x 23 cm digital pigment print on Hahnemühle pearl paper.

In Havana, I found some bananas hanging on a huge, elegant imperial palm tree, tied with a red ribbon. It was when I discovered that besides being the symbol of Cuban constitution, printed on the back of some C.U.C coins, the imperial palm tree is also the tree of Sango. And Sango, the King of justice, likes bananas. The status symbol of the imperial palm tree was also spread during colonial times in Brazil. King John VI of Portugal planted the first one in the Rio de Janeiro Botanical Gardens and forbade the selling of its seeds. But Sango intervened: at night, enslaved people would climb the tall trunks and steal the seeds, which they would sell the next day. Bit by bit, seeds were transformed into coins, used to buy their freedom.

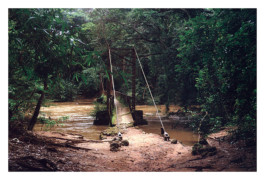

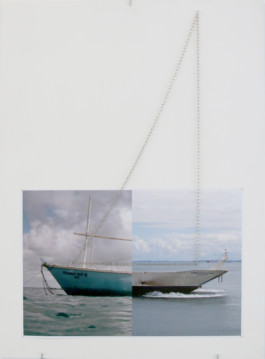

Yemanjá and Zumbi, 2019 - 2021

Photograph 33 x 50cm, chain

Iyemoja is one of the deities of water, in Brazil, she is the Sea. According to the Yoruba mythology, she once disappeared in the city of Shaki, Nigeria and transformed into the Ogun river, that flows to the Ocean. Zumbi dos Palmares was a Brazilian black man, born at Quilombo dos Palmares, on 20. November 1695. He died fighting for freedom for black people. His head was exhibited in a public square of Recife, Pernambuco. Today, he is a symbol of resistance, and 20. November is “Black consciousness day in Brazil, a National Holiday (Law 12519, 2011, passed by president Dilma Rousseff). The boat named after him transports people from Salvador to Itaparica Island every day.

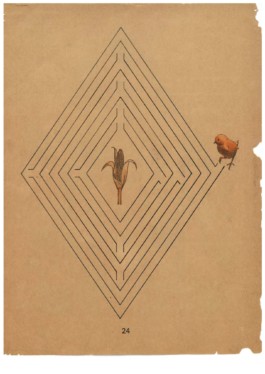

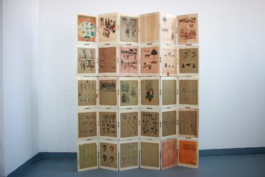

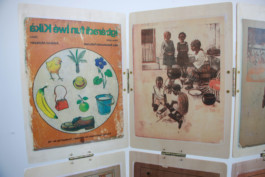

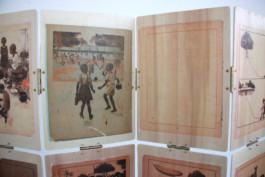

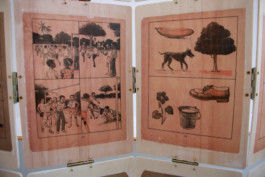

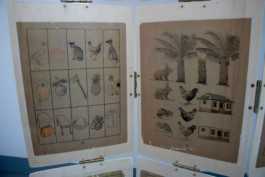

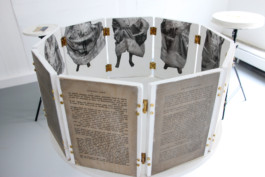

Ìgbáradì fun Ìwé kíkà, 2020

30 foto transfer on 21 x 29,7 cm woodplates, metal hinges

The 1980 schoolbook that teaches Yoruba to the kids, found in a bookshop at Ejigbo, Osun State, Nigeria turns into a monument.

Street poems, 2020

Wood and photo-transfer. 40cm diameter.

Socialist sentences found in the streets of Havana join extracts of the Cuban Constitution and some images of the Caribean Sea, Playa de la Calle 16, in Miramar, district of Havana.

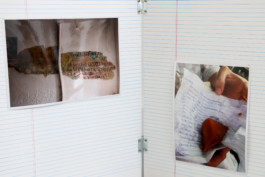

Logbook, 2020

02 Woodplates 59,4 x 42 cm, 2 metal hinges, 1 Photo transfer 21 x 29,7 cm, 1 Photograph 20 x 30 cm.

A poem by artist and priestess Susanne Wenger, found on the wall of her former home in Nigeria: “Nun sind letzendlich Vögel doch eingeladen, i.e. Jenseits Zeit als es da noch Vögel gab” or “Now birds are finally invited, i.e. from beyond time when there were still birds” with a page from a schoolbook used to serve the acara, where we can read “the earth revolves around the sun, sun-star”.

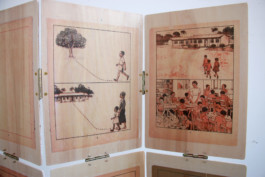

Biografia de una isla, 2020

1m x 21,5 cm I 8 woodplates, metal hinges.

Cuba has an ambiguous relationship with art and reading. Everything published locally is state-financed, a blessing, but also a form of control.

Since publications are not so abundant, it’s not unusual to find very old ones people take care of. In my endless walks through Miramar, I found ‘Biografia de una isla’ in a home-made bookshop in a veranda.

The preface is about an Indigenous guy who wakes up 500 years later in the window of a downtown Havana museum and starts analysing the changes after colonialism started. It’s a speculative fiction that ends with the sentence “Y desapareció”. I transferred the pages of this preface and created a continuation to the story by adding images of santera Raiza, whom I visited many times in the suburbs of the city. Once she dressed a “traje de gala”, the gala dress one is only allowed to wear once in a lifetime, in the initiation process of Santería. She wanted so much to show me how beautiful it looked like, that she asked her neighbour for her dress and put it on. She then danced until she disappeared.

Even the silences ascend to heaven, 2021

Installation with 07 plaster sculptures in variable sizes

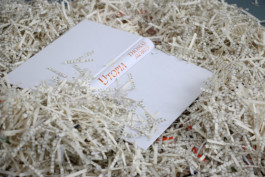

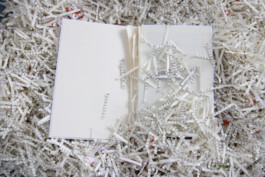

Broken Utopia, 2020

Bookcover and pages in pieces 65 x 65cm I Video, full HD, color, sound, 14’40’’

The 1516 book, written by Thomas More, coins the word Utopia, an ideal but impossible society. To shred the pages of Utopia is to create an alternative to what has been instituted and to inaugurate a new Utopia that questions the colonial modus operandi, continually being reproduced when we think about plans for conquering space.

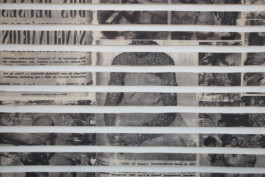

The brides of the bloodthirsty gods, 2020

Woodplate 82 x 62 cm, photo transfer.

The work departs from extracted images and texts published in 1951 at Brazilian Journal “O Cruzeiro”. Written by Arlindo Silva, with photos by José de Medeiros, the paper unravels for the first time in the big press several secrets of initiation processes at candomblé, Afro-Brazilian religion, and its publication was very controversial. Therefore, the choice to reproduce it cut and with the text backwards, creating a double mistery over this historical document. The photo-transfer technique mirrors the image, similar to what happens in the transe, when one becomes its back or receives another head. The work aludes to the candomblé houses own learning: what one is authorized to know and what needs more time to be unveiled.

Texts

Contradictions of the trip,

conditions of the trip

"[...] les cartes se superposent de telle manière que chacune trouve un remaniement dans la suivante,

au lieu d'une origine dans les précédentes: d'une carte à l'autre,

il ne s'agit pas de la recherche d'une origine,

mais d'une évaluation des déplacements."

— Gilles Deleuze— Deleuze

By Maykson Cardoso

PhD candidate in Art History at Federal University of Rio de Janeiro and is based in Berlin.

1.

In order to understand the "triangular cartographies" that Ana Hupe presents, we must know, first of all, that we will not find in them anything similar to maps, at least as far as the representations of geographical divisions are concerned. These are part of another kind of cartography: if they are maps, they are maps of intensity, with which the artist puts us in front of that which crossed her, while she herself crosses through Brazil, Cuba, and Nigeria. Her cartographies are composed of photographic records, films, or even small objects that she collected along the way, imbued with her experiences and perceptions, and rearranged from the criterion or method of "triangulation". That is: her way of approaching, superimposing or juxtaposing these elements with the objective of showing or creating a common ground between them and, consequently, between the places from which they come.

The first meaning of this "triangulation" stems from relationships between these three countries, marked by the colonial violence that inevitably founds their common ethos; a violence whose effects are still valid today, going by names such as extractivism, slavery, exploitation, or even "progress," capitalism, necroliberalism¹. Thus, "triangulation" as a method, which also reverberates in the form of the triangle that appears in some of these works, is more than the mere exercise of those who dedicate themselves to finding connections between travel destinations: it is a means of shaping this common history, of denouncing the first point of intersection between the history of these places, which curiously appear on old maps such as the Triangular Trade that laid the foundations of geopolitics and, therefore, of the extractivist and slave economy of the colonial period.

By observing cultural aspects of the traditional Yoruba religion that arrived in Brazil and Cuba with the expansion of the slave market that enslaved thousands of black Africans in the "New World," Ana Hupe does not want to find the origins of the religion, but, rather, to evaluate, as Deleuze says in the epigraph, its displacement: what is preserved and what changes with respect to the Yoruba religious tradition from one place to another over time? What were the tactics used to ensure the survival of the traditional religion, despite all the prohibitions in the new continent? Some clues become evident, for example, in the sacred chants of the Brazilian candomblé or the santería in Havana: chants that a person of Yoruba ethnicity can often only recognize today thanks to the melody that has been maintained over the centuries, since the language only survives in a few liturgical words.

2.

It is necessary to look at these works searching for what is revealed in them as an index of conflict, of contradiction. For example, in Street poems, the artist brings us phrases found in the streets of Havana such as "Trincheras de ideas valen más que trincheras de piedras" (Trenches of ideas are worth more than stone trenches) and "Brillamos con luz propia" (We shine with our own lights), superimposed over passages from the Cuban Constitution, sold in a newspaper for 1 CUC in several kiosks scattered around the city. The first phrase comes from José Martí, founder of the Cuban Revolutionary Party and organizer of the Cuban War of Independence at the end of the 19th century; the second comes from one of the verses of Pablo Milanés' Canción por la Unidad Latinoamericana (Song for Latin American Unity), whose last stanzas recall Latin American revolutionary leaders - Simón Bolívar, José Martí himself, and Fidel Castro - to call for the unity of the continent:

Lo que brilla con luz propia nadie lo puede apagar

Su brillo puede alcanzar la oscuridad de otras costas

Qué pagará este pesar del tiempo que se perdió

De las vidas que costó, de las que puede costar

[...]

Bolívar lanzó una estrella que junto a Martí brilló

Fidel la dignificó para andar por estas tierras

Bolívar lanzó una estrella que junto a Martí brilló

Fidel la dignificó para andar por estas tierras³

But if these utopian ideals that founded the revolution in that country are quoted there, in another work, Ana Hupe offers us the image of a "Broken Utopia"; the artist takes the Utopia of Thomas Morus - a book launched in the 16th century that tells the fictitious story of an "ideal society" -, rips off its cover, spikes its pages and arranges them like a pile of paper the floor. At first sight, her gesture may seem like rejection of the "utopian idealism" to surrender to the melancholy of the world, but at the same time it is also the gesture of recognition of this utopia as something insufficient: one must tear it apart, not to discard it afterwards, but to seek other ways of thinking about it and rebuilding it.

To the shredded pages is added her Biografía de una isla, a work in which the artist presents us excerpts from the book of the same name by Emil Ludwig. In this book, she tells us, the author starts from "one of the legends of the myth of origin in Cuba, narrated by an indigenous man who was locked in a museum in downtown Havana 500 years ago. He suddenly wakes up and begins to analyse the changes since colonisation.” Perhaps it comes from a look that is no longer just that of the European man, that possibility of rethinking and rebuilding our broken utopias. Those that are no longer guided only by the lyrics of a Thomas Morus, of a Karl Marx et caterva, but that are also guided by the voice of the native who takes the floor to narrate, himself, the colonial violences.

That Emil Ludwig is another European man to recover the myth of origin of the Caribbean island, is just another contradiction that appears, as said, in other works; something that the artist seems to leave marked by making use of the photo-transfer technique, which consists in transferring the contents of pages of books, newspapers or photographs, gluing them on the surface of the wood with a special product. The transferred content remains there, fixed, but appears inverted, mirrored, with the appearance of an old fresco, a peeled wall or a forgotten and worn out lamppost. In the specific case of texts, if this technique does not make it impossible to read them, at least it makes it more difficult; and what could be only a formal detail gains the sense of a disruptive gesture similar to that of punching the pages of Utopia. If the text there resists, it resists as rest; and the form with which it is presented to us also comes from that action of destroying something without then discarding it, because there is no other possibility than that of working with what remains.

Transfer is also the technique used in "The Brides of the Bloodthirsty Gods", that brings to light a journalistic article by “O Cruzeiro”, published in 1951. In this article, whose title - the same one that gives the work its name - is already somewhat sensationalist, the first journalistic record of candomblé initiation rituals in Brazil was made. The article caused controversy due to the exposure of a ritual restricted to a few initiated. The ambiguity of its title places women as brides of violent gods, a representation beyond contempt and misrepresentation of the orishas worshipped in religions of African matrix. Aware of this, Ana Hupe retrieves the pages of the magazine in which the article was published, cuts out the photographs, transfers them to wood, shreds them up and reassembles them, preserving, between the shreds, gaps. If in some way she gives us to see those pages, she makes the same gesture on them: she does not deny the existence of such a document and, neither, its content of violence; she accuses it of its existence and leaves the marks of its non-conformity on it.

In this game with contradictions, images become "dialectic image", or "critical image" - Walter Benjamin's concept which, in Brazil, has been constantly taken up from Didi-Huberman's point of view. One can think of this image as one that is something and its opposite simultaneously. When we look at them, they confront us, giving us back a look that also questions us. If Ana Hupe presents to us images of this order, this can lead us to think that she has no naive understanding of culture; every monument of culture, as Benjamin warned us, is also a monument of barbarism. To refuse the inherent game between culture and violence - especially that of domination - would be like throwing the dust under the carpet, repressing the trauma to avoid its elaboration. It is certainly difficult to confront it, but there is no other exit to account for our past. It is from such a position that contradiction also gains a positive value: it demarcates the point where this "elaboration"² is necessary.

3.

In “Hegel and Haiti”, Susan Buck-Morss takes up the famous "dialectics of the lord and the slave" to show, based on the historical context, that Hegel had probably formulated this dialectic inspired by information from the Haitian Revolution. Although he never mentioned any reference in this regard, in analysing the evidence that allows him to build this hypothesis, the American philosopher questions:

Either Hegel was the blindest of all the blind freedom philosophers in Enlightenment period in Europe, leaving Locke and Rousseau behind in his ability to deny reality under his nose [...], or Hegel knew - of the royal slaves who were victorious in their revolt against their royal masters - and deliberately elaborated the dialectics of landlord and servitude within their contemporary context. 〈BUCK-MORSS, S. Hegel e o Haiti. São Paulo: N-1. p. 78.〉

This hypothesis demonstrates how much the freedom proclaimed by the European Enlightenment (Aufklärung), one of the ideals that sustained the French Revolution, had nothing "universal" as it intended; when the Haitian Revolution wanted to use these same ideas to free itself from its condition as a French colony, Napoleon sent his troops to prevent independence. The universality of these values, therefore, was restricted.

We must remember that the “footnotes” first appeared as an answer to the German context; so they are also part of a strategy to make what is still unknown or ignored to the spirit forged by this European Aufklärung a little more understandable. There are ways of thinking or making the world that are often still read under the key of the "exotic", the "eccentric".

Unlike the colonies, which have experienced the violence of colonisation and are still dealing with its effects today despite their independence, Europe still lacks stronger positions that can question its hegemony. Positions that could destabilise the placidity of its domains from within by bringing in elements from the outside. Here I include the epistemological domain, as demonstrated by Susan Buck-Morss, which is still acting as a substratum for the European Union, built on these "universal values". These footnotes, a paratex common to the most complex texts, under no circumstances lead to the reading of their texts-work; with them, the artist simply wants to ensure a minimum coefficient for their intelligibility.

¹ I borrow the term used by Achille Mbembe in an interview to Folha de São Paulo. The philosopher speaks of the effects of the coronavirus pandemic; he criticizes the way neoliberals treat people's lives, reducing them to a number in statistics. Thus, he relates his already widespread concept of "necropolitics" - roughly: the politics of governments that determine who can live and who should die - to the economic model in necroliberalism, which places the economy above everything and everyone. https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/amp/mundo/2020/03/pandemia-democratizou-poder-de-matar-diz-autor-da-teoria-da-necropolitica.shtml

² In German, "Aufarbeitung der Vergangenheit" - the "elaboration" or, as Jeanne Marie Gagnebin translates it into Portuguese, "perlaboration of the past" - is the title of one of the texts in which Theodor W. Adorno proposes a series of necessary steps to understand and confront, in the German context, Nazism and its effects without repressing it, that is, without forgetting or pretending it never existed.

Fremd in der Heimat

von Katharina Warda

My body is made of stars

Lit by their futures passed

Weighing down from above,

Untold stories

My body is made of stars,

An impatient supernova

Ready to explode!

Ready to be told!

Fremdenfeindlich nennt man es in der Zeitung als im Jahre 1994 Rufe wie “Deutschland den Deutschen. Ausländer raus” durch die Straßen schallen. Auch auf Bernaus Straßen hört man “Sieg Heil”-Rufe und “Asylanten wie Juden vergasen”. Oder zwanzig Jahre später, als ein Schwarzer Bernauer körperlich angegriffen und rassistisch beleidigt wird. Fremdenfeindlichkeit heißt es im TV als im Jahr 1991 Menschen aus Hoyerswerda drei Tage lang Asylunterkünfte in Brand stecken und Steine und Molotowcocktails in Wohnheime von ehemaligen Vertragsarbeiter:innen werfen, um sie zu töten. Die Fremdenfeindlichen, so nennt meine Mutter die Menschen, die mich im Alter von sieben Jahren auf dem Heimweg von der Grundschule mit dem N-Wort beschimpfen, mich mit Steinen bewerfen und über den Schotterweg nach Hause jagen. Dieses Zuhause ist aber nicht “Afrika”, wie sie sagen. Dieses Zuhause ist keine “Buschhütte”, “kein wilder Jungel”, wie sie denken. Das Land, aus dem ich komme und in das sie mich mit Flüchen zurückwünschen ist die DDR, ist Deutschland, ist Ostdeutschland, genau wie ihres.

Dieses “Afrika”, von dem sie sprechen, gibt es gar nicht. Auch Emanuel, Manuel und Imanuel, die als mosambikanische Vertragsarbeiter in die DDR migrierten, diese mit ihren ausbleibenden Löhnen ökonomisch sicherten und 1991 Hoyerswerda überlebten, kommen nicht aus diesem “Afrika”. Sie kommen aus einem realen Land eines realen Kontinents, nicht aus “der Fremde”. Dieses “Afrika” ist eine Erfindung unserer Kultur. Es ist das imaginative Fremde und hat als solches seine Funktion. Es ist exotisch, glitzernd, schaurig und schön. In Form von Weltausstellungen, Zoos und in Botanischen Gärten. Es ist ein anziehender Teil unserer Kultur, aber nur solange es beherrschbar wirkt. Solange es seinen Platz kennt. Solange es klein, unmächtig, ja ohnmächtig erscheint gegenüber seinem Gegenpol, dem “Heimischen” und dieses damit erst genau zu dem macht, wie wir es wahrnehmen: vertraut, sicher, überlegen. Das Fremde darf diese Vertrautheit, diese vermeintliche Überlegenheit, die so viel Sicherheit schenkt nicht stören. Sie darf sie nur rückversichern und dazu gehört auch die Gewalt gegen “Fremde”. Dafür muss sie da und nicht da, sichtbar und unsichtbar sein. So hängt an jenem wohligen Gefühl von Heimat auch immer ein Preis, der bezahlt werden muss. Der Preis der Ausgrenzung, der Unsichtbarmachung und notfalls der Vernichtung. Aber praise be, ihn zahlen die Anderen, die “Fremden”.

In kleinen Glaskisten kommt das “Fremde” mit der Kolonialzeit nach Deutschland und lässt den Botanischen Garten entstehen. Darüber erzählt der Beitrag “Nach dem Warmhaus” (2021) von Anna Lauenstein und Max Hilsamer. Aus einfachen Pflanzen werden nun einheimische Sorten und Neobiota, “fremde, nicht-einheimische Pflanzen”. Ein Stück deutsche Weltmachtsfantasie, an die sich Kolonialwaren.

Menschenzoos, Mohren-Inszenierungen, Gewaltexzesse und die Erfindung des Rassismus, des “Heimischen” und des “Fremden” reihen. Das Fremde und seine ihm eingeschriebene Abwertung leckt unsere nach Aufwertung lechzende Wunden, pinselt uns die dicken Bäuche und sagt unserem Ego, wer und was wir sind: überlegen. Dazu brauchen wir das Fremde. Doch das Fremde braucht uns nicht und übt Widerstände, manchmal an den ungewöhnlichsten Stellen. Verschleppte Pflanzen brechen aus dem Botanischen aus. Schaffen es in die Abwasserleitung und von dort in viele europäische Flusssysteme. Auf dem Marktplatz meiner Heimatstadt rennen die ehemals vietnamesischen Vertragsarbeiter 1992 nicht mehr davon als sie von stolzen Deutschen mit Eisenstangen angegriffen werden. Sie bleiben stehen und schlagen als letzte Abwehr zurück.

Und in Brasilien, dem einst von Portugal kolonialisierten Land, das vom Sklavenhandel lebte, schreibt sich die nigerianische Yoruba-Kultur ganz selbstverständlich ins Heimische ein und lebt in ihr fort. In Ana Hupes Beitrag “Footnotes to triangular cartographies” (2019-2021) spannt sie ein diskursives Netz aus Riten, Feiertagen, Gottheiten und Erzählungen, welches Kategorien wie “heimisch” und “fremd” ad absurdum führen. Die sonst unsichtbare Yoruba-Kultur Brasiliens wird hierdurch sichtbar als das, was sie ist: Schon immer da gewesen und bereit gehört, gesehen zu werden.

Kultur ist nirgends ein homogener Raum, dem ein homogen “Fremdes” gegenübersteht. Sie ist und war von Jeher ein polyphoner Kosmos, in dem Widersprüche aufeinandertreffen, miteinander leben und Verbindungen eingehen. Ein Weltraum der Aushandlungen, Inspirationen und Verschmelzungen und somit ein Habitat des Gedeihens. Eine solche Tafel der Aushandlungen, ein Tisch an dem jede:r Platz findet und sich als Teil der Vielfalt wahrnehmen kann, beschreibt Gudrun Sailer mit ihrem Beitrag “Fruchtbare Inseln, vom Senden und Empfangen” (2021).

Und genau hier im Kosmos der Vielfalt, im Raum des schon immer dagewesenen und der ständigen Bewegung. Hier wo “fremd” und “heimisch” verschwinden, weil es sie nicht braucht. Hier, wo an ihrer Stelle Vielfalt wie Blumen blüht und es gegenseitige Wertschätzung wie Sternschnuppen regnet. Hier in diesem (noch) fremden Kosmos ist meine Heimat.