Do Céu e da Pedra, 2024

Exhibition at Portas Vilaseca Galeria, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

01.08.24 - 06.09.24

In the Hinterlands the stone cannot teach,

And if it did, it wouldn’t teach anything;

There one does not learn the stone, there the stone,

A birth stone, is buried within the soul.

[João Cabral de Melo Neto, A educação pela pedra]

How many stones make up our lives? How much sky makes up our ground? We imagine the immanence of the stone: that which it withholds, its impenetrable interiority, its invisible mutability, the material manifestation of the divine. We consider the sky’s transcendence: what the sky projects onto the imagination, the immaterial, the path beyond. Yet, there’s the transcendence of the stone: the stone that knows itself to be a stone, the throw. And the sky’s immanence: the crumbling utopia.

Through screen printing, fabrics, embroidery, found objects, and film frames, Dreaming Dashes, Ana Hupe’s solo show, weaves thoughts on immanence and transcendence, the mystic surrounding shapes, and the revolution of movement. Each work is a story brought to life by the encounter with a sign or the silence between the lines of a text, to be combined with experiences the artist uncovers during her travels. Between the stone and the sky, we find the entanglements of colonial relationships between Brazil, West Africa, and Europe – particularly Germany, where the artist lives. Hupe uses critical fabulation as a methodological guide, a process that links historical research to the “power of invention” - as writer Saidiya Hartman puts it – to recount forgotten facts and facets of people’s lives, opening new pathways for historical reparations that go beyond the object itself.

Following this speculative journey, the ground floor belongs to the stone: foundation-territory-throw, the one that holds the power to trigger revolutions. Hupe chose to watch the life of rocks and find a way to dignify them, recognizing their geological cycles, which extend beyond the span of human existence, and state – countering natural science’s distinctions between living and non-living – that stones are endowed with a build-up of life.

In this perspective, stones tell different stories; they are amalgamations of time, code, and composition. In the series If you throw a Mediterranean Stone, Hupe uses a study by theosophical writer Charles Webster Leadbeater (1854-1934) that, in an attempt to understand how magical thinking could have tangible effects on the real world, systematized the human energy field into a color chart to define thought-forms possibly visible to mediums. Hupe hijacks this same chart to make the stones she collected from the Mediterranean Sea speak, composing an oracular poem through its colors.

The Fon people’s Voudoun practices refer to stones; some are understood to contain sacred powers and are used to conjure or represent the Lwa spirits. In Alchemy, amethysts, amazonites, crystals, and other stones summon Voudoun’s symbols and motifs, which the artist found throughout the streets of Benin, where Voudoun is still intensely practiced. We see especially those inspired by Mawu-Lisa, an androgynous creator entity that carries the day and the night. As seen from a worldview in which everything is connected, stones become focal points between the visible and the invisible, the physical and the spiritual.

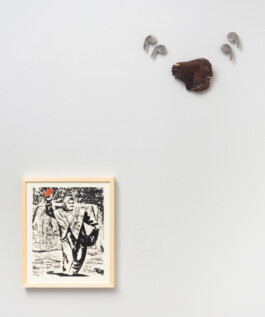

Cultures mutually influenced each other through the flux of colonial histories, though these exchanges are rarely remembered. Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel’s Phenomenology of the Spirit, published in 1806, is one of the cornerstones of German idealism and the European Philosophical school. But, as suggested by Susan Buck-Morss, some of its central theses were inspired by the Haitian Revolution that happened a few years prior, between 1791 and 1804. Hegel, in his famous master-slave dialectic, invoked the Haitian revolutionaries’ “freedom or death” motto to explain that self-awareness, this recognition of oneself before another within a high state of knowledge, is present in the fight for freedom. In the work When Hegel meets Toussaint L’Ouverture carrying a Màkpo, Ana Hupe shows a Hegel, in the printed pages of his own Phenomenology of the Spirit, haunted by Voudoun symbols and by the image of Toussaint L’Ouverture - the Haitian Revolution’s greatest leader - carrying a Màkpo – an instrument used to authenticate messages sent by the kings and queens of the Dahomey Kingdom (present-day Benin), also used as a defense weapon. Vilified and decharacterized intending to weaken and dominate this practice, traditional Voudoun practice was the driving force to break away from slavery and erect the world’s first black republic. The first assemblies that launched the Haitian Revolution were organized alongside Voudoun priests and their teachings about nature and freedom guided the Haitian people to victory. To imagine the symbolic return of the liberating Voudoun cosmology to Western philosophical thought is, in a way, revenge and an allegorical reparation.

Aníbal Quijano reminds us of how the coloniality of power subtly acts in the continuity of its methods for domination and operates within a web of political, social environmental, and racial relations. To unveil this hidden facet of coloniality, Ana Hupe uses the butterfly effect metaphor, which explains the relationships between apparently distant events within systems that are highly susceptible to any variation. Butterfly Effect stems from a reading: A book by Eliane Brum that mentions biology studies on the fading of Amazonian butterfly colors as they mimic the burned forests and urban expansion. The concrete headstone bearing the butterfly shapes forms an equation alongside other elements that make us aware of the effect’s differing degrees, unnoticeable at times due to its overwhelming reach. This equation is cyclical and synthetic, resolving it entails admitting the key role of aesthetic enjoyment, in this case, the association of environmental crisis and a much-needed reflection of colonialism.

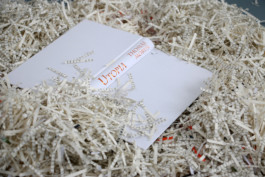

Hupe often works in close connection to books and, concurrently, we notice actions that seek to desacralize them and show them as battlegrounds: pages torn from books, entire books shredded. The book is a mediator of worlds, a compiler and transmitter of knowledge, but also the quintessential symbol of the colonialist imperial project. According to Walter Mignolo, the book is one of the most common technologies for recording discourses in Western societies. As a tool for thought systematization, the book received free reign over the hierarchy of knowledge. As if it could contain all forms of knowledge, others not contained therein being considered inferior.

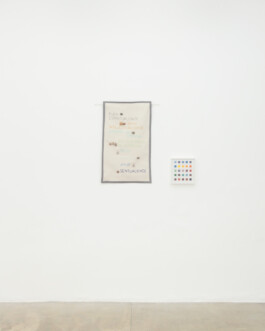

This ambiguous act of respect and profanation leads us to the show’s third floor: the sky. Like phantasmagoric beings, objects belonging to peoples from South America and Western Africa are printed onto indigo blue fabrics in the Transatlantic Crossroads series. Feathered Karajá headdresses, Yoruba masks from Benin, and thrones belonging to Oba Esigie and King Béhanzin, among others. Seized objects, now kept in German museums, are bearers of a history of encounters and outbreaks of violence. Here, they receive a new lease on life as textile prints, as a way to operate a poetics of restitution, as stated by the artist: she hopes to be able to insert them into local West African textile industries so they can be reappropriated and bought by the people. In Voudoun, blue is frequently associated with the connection between the physical and spiritual worlds, and its indigo dye strongly binds it to the cultural heritages of Benin and Nigeria.

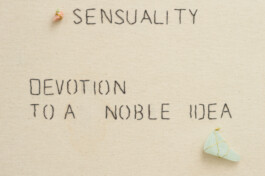

The stones are now a textile knit, capable of wrapping, covering, moving to the wind’s desire. Codes are inscribed into their mesh, which, across many cultures, form non-phonetical systems of communication, with historical retellings and epistemologies that diverge from Western ones. When considering Quechua textile culture, Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui talks about the narrative woven into them, seemingly abstract to the eyes of the uninitiated, as dynamic forms of cosmovision redistribution. In her fabrics, Ana Hupe proposes a form of sharing enabled by a form-device distinct from books or written language.

The printed fabrics can also teach us about German ethnographic practices; they are an ethnographer’s ethnography of sorts. In the late 19th century, travelers from the recently unified Germany were responsible for establishing the first contact between Europeans and South American peoples dwelling in areas of difficult access. While they gathered objects as evidence for the existence of those cultures – and so they, themselves, could gain prestige -, they provoked transformations within those groups as they were introduced to European culture. Furthermore, 1884 was the year of the Berlin Conference, which regulated the colonization of the African territory, known as the “Scramble for Africa”, and inaugurated a new phase of European Imperialism. A few years later, 1897 saw one of history’s best-known plundering of artworks: the punitive British expedition to Benin, Nigeria, when over 4.000 artifacts were looted from the royal palace of Oba Ovonramwen Ngobaisi, among them the famous Benin Bronzes, created in the 14th century by artists from the Edo people. Official records state that 1.027 went to British museums while 1.118 were purchased by German collections. Calls for their restitution were made and continue to this day. In December of 2022, Germany returned twenty-two works of art in its possession to Nigeria, leaving empty exhibits in some museums or displaying copies in their places. The French state repatriated twenty-six bronzes in 2021, after a report published by researchers Felwine Sarr and Bénédicte Savoy. When referring to recent restitutions, Savoy speaks of a “boomerang return” – a movement that, after years of denials and absent mindedness, returns with exponential force: “restitution, decolonization, social justice, and patrimonial justice go hand in hand.” (SAVOY, 2023).

Statues never die, contrary to what Alain Resnais, Chris Marker, and Ghislain Cloquet believed in the 1953 film-essay Statues Also Die. Ariella Aïsha Azoulay talks about how these objects, so thoroughly guarded and documented in European museums, are just slumbering as they wait to be returned to their territory. They are not mere ethnographic artifacts – a reductionist approach to which they were submitted by the coloniality of knowledge -, but beings endowed with community and spiritual mediation in their place of origin. The museum-institution, heir to modern colonial thinking, severs the ties between objects and the context of their production. Also in 1953, the German Theodor Adorno decreed their downfall, as they enclose objects that possess no vital ties to their observer. Ethnographic museums still present culture as patrimony seen through an objective lens. By removing an object from and location and transferring it to another, placing it inside a glass case, the museum institutionalizes the cultural “other” and lays down separations, categories, and chronologies. In that sense, the poetics of restitution Ana Hupe operates presents the captured objects as living things, inseparable from their context, so the museum could not be their final destination, but a stop along the way, a passing place for this speaking object.

Juliana Gontijo – curator

PS.: As I encountered the works that make up this show, I listened to Ana’s many stories about encounters and separations, and what drove her to think of them as art. I’ll now tell one of these stories: in one of her trips to Benin, Ana Hupe was waiting for the confirmation of a visit to a descendant of queen Tassi Hangbé, the Kingdom of Dahomey’s first Amazon warrior. Upon being summoned by the queen, she found herself wearing jeans and had to stop in a shop and purchase a fabric (pagne) to wrap herself in. She found one patterned with throne drawings, a choice the queen approved of. It was then that she stumbled across the idea of transforming some of the looted objects into drawn fabrics.

References

BUCK-MORSS, Susan. Hegel and Haiti. Critical Inquiry, Vol. 26, No. 4.

(Summer, 2000), pp. 821-865.

HARTMAN, S. Vênus em dois atos. Revista Eco-Pós, [S. l.], v. 23, n. 3,

p. 12–33, 2020. DOI: 10.29146/eco-pos.v23i3.27640. Available in: https://revistaecopos.eco.ufrj.br/eco_pos/article/view/27640

MIGNOLO, Walter. O lado mais obscuro do Renascimento. Em: universitas humanística [online]. 2009, n.67, pp.165-203. ISSN 0120-4807. Available in: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?pid=S0120-48072009000100009&script=sci_abstract&tlng=pt.

QUIJANO, Aníbal. (2005). Colonialidad y modernidad-racionalidad.

In: Perú Indígena, vol. 13, no. 29, Lima, 1992.

SANDOVAL, Lorenzo. Weaving Waves. A platform on text, textile and technology.

In: Siegfried Zielinski and Daniel Irrgang (coords.). Node «Materiology and Variantology: invitation to dialogue». Artnodes, no. 34, UOC, 2024.

Available in: https://doi.org/10.7238/artnodes.v0i34.426915.

SAVOY, Bénédicte. O Retorno do Bumerangue. [Interview with] Márcio Seligmann-Silva. Revista Select, 13/03/2023.

Available in: https://select.art.br/o-retorno-do-bumerangue/

Un-Documented: Unlearning Imperial Plunder. Filme de Ariella Aïsha Azoulay.

35 min. 2019. Available in: https://vimeo.com/490778435.

Do Céu e da Pedra, 2024

Exhibition at Portas Vilaseca Galeria, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

01.08.24 - 06.09.24

In the Hinterlands the stone cannot teach,

And if it did, it wouldn’t teach anything;

There one does not learn the stone, there the stone,

A birth stone, is buried within the soul.

[João Cabral de Melo Neto, A educação pela pedra]

How many stones make up our lives? How much sky makes up our ground? We imagine the immanence of the stone: that which it withholds, its impenetrable interiority, its invisible mutability, the material manifestation of the divine. We consider the sky’s transcendence: what the sky projects onto the imagination, the immaterial, the path beyond. Yet, there’s the transcendence of the stone: the stone that knows itself to be a stone, the throw. And the sky’s immanence: the crumbling utopia.

Through screen printing, fabrics, embroidery, found objects, and film frames, Dreaming Dashes, Ana Hupe’s solo show, weaves thoughts on immanence and transcendence, the mystic surrounding shapes, and the revolution of movement. Each work is a story brought to life by the encounter with a sign or the silence between the lines of a text, to be combined with experiences the artist uncovers during her travels. Between the stone and the sky, we find the entanglements of colonial relationships between Brazil, West Africa, and Europe – particularly Germany, where the artist lives. Hupe uses critical fabulation as a methodological guide, a process that links historical research to the “power of invention” - as writer Saidiya Hartman puts it – to recount forgotten facts and facets of people’s lives, opening new pathways for historical reparations that go beyond the object itself.

Following this speculative journey, the ground floor belongs to the stone: foundation-territory-throw, the one that holds the power to trigger revolutions. Hupe chose to watch the life of rocks and find a way to dignify them, recognizing their geological cycles, which extend beyond the span of human existence, and state – countering natural science’s distinctions between living and non-living – that stones are endowed with a build-up of life.

In this perspective, stones tell different stories; they are amalgamations of time, code, and composition. In the series If you throw a Mediterranean Stone, Hupe uses a study by theosophical writer Charles Webster Leadbeater (1854-1934) that, in an attempt to understand how magical thinking could have tangible effects on the real world, systematized the human energy field into a color chart to define thought-forms possibly visible to mediums. Hupe hijacks this same chart to make the stones she collected from the Mediterranean Sea speak, composing an oracular poem through its colors.

The Fon people’s Voudoun practices refer to stones; some are understood to contain sacred powers and are used to conjure or represent the Lwa spirits. In Alchemy, amethysts, amazonites, crystals, and other stones summon Voudoun’s symbols and motifs, which the artist found throughout the streets of Benin, where Voudoun is still intensely practiced. We see especially those inspired by Mawu-Lisa, an androgynous creator entity that carries the day and the night. As seen from a worldview in which everything is connected, stones become focal points between the visible and the invisible, the physical and the spiritual.

Cultures mutually influenced each other through the flux of colonial histories, though these exchanges are rarely remembered. Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel’s Phenomenology of the Spirit, published in 1806, is one of the cornerstones of German idealism and the European Philosophical school. But, as suggested by Susan Buck-Morss, some of its central theses were inspired by the Haitian Revolution that happened a few years prior, between 1791 and 1804. Hegel, in his famous master-slave dialectic, invoked the Haitian revolutionaries’ “freedom or death” motto to explain that self-awareness, this recognition of oneself before another within a high state of knowledge, is present in the fight for freedom. In the work When Hegel meets Toussaint L’Ouverture carrying a Màkpo, Ana Hupe shows a Hegel, in the printed pages of his own Phenomenology of the Spirit, haunted by Voudoun symbols and by the image of Toussaint L’Ouverture - the Haitian Revolution’s greatest leader - carrying a Màkpo – an instrument used to authenticate messages sent by the kings and queens of the Dahomey Kingdom (present-day Benin), also used as a defense weapon. Vilified and decharacterized intending to weaken and dominate this practice, traditional Voudoun practice was the driving force to break away from slavery and erect the world’s first black republic. The first assemblies that launched the Haitian Revolution were organized alongside Voudoun priests and their teachings about nature and freedom guided the Haitian people to victory. To imagine the symbolic return of the liberating Voudoun cosmology to Western philosophical thought is, in a way, revenge and an allegorical reparation.

Aníbal Quijano reminds us of how the coloniality of power subtly acts in the continuity of its methods for domination and operates within a web of political, social environmental, and racial relations. To unveil this hidden facet of coloniality, Ana Hupe uses the butterfly effect metaphor, which explains the relationships between apparently distant events within systems that are highly susceptible to any variation. Butterfly Effect stems from a reading: A book by Eliane Brum that mentions biology studies on the fading of Amazonian butterfly colors as they mimic the burned forests and urban expansion. The concrete headstone bearing the butterfly shapes forms an equation alongside other elements that make us aware of the effect’s differing degrees, unnoticeable at times due to its overwhelming reach. This equation is cyclical and synthetic, resolving it entails admitting the key role of aesthetic enjoyment, in this case, the association of environmental crisis and a much-needed reflection of colonialism.

Hupe often works in close connection to books and, concurrently, we notice actions that seek to desacralize them and show them as battlegrounds: pages torn from books, entire books shredded. The book is a mediator of worlds, a compiler and transmitter of knowledge, but also the quintessential symbol of the colonialist imperial project. According to Walter Mignolo, the book is one of the most common technologies for recording discourses in Western societies. As a tool for thought systematization, the book received free reign over the hierarchy of knowledge. As if it could contain all forms of knowledge, others not contained therein being considered inferior.

This ambiguous act of respect and profanation leads us to the show’s third floor: the sky. Like phantasmagoric beings, objects belonging to peoples from South America and Western Africa are printed onto indigo blue fabrics in the Transatlantic Crossroads series. Feathered Karajá headdresses, Yoruba masks from Benin, and thrones belonging to Oba Esigie and King Béhanzin, among others. Seized objects, now kept in German museums, are bearers of a history of encounters and outbreaks of violence. Here, they receive a new lease on life as textile prints, as a way to operate a poetics of restitution, as stated by the artist: she hopes to be able to insert them into local West African textile industries so they can be reappropriated and bought by the people. In Voudoun, blue is frequently associated with the connection between the physical and spiritual worlds, and its indigo dye strongly binds it to the cultural heritages of Benin and Nigeria.

The stones are now a textile knit, capable of wrapping, covering, moving to the wind’s desire. Codes are inscribed into their mesh, which, across many cultures, form non-phonetical systems of communication, with historical retellings and epistemologies that diverge from Western ones. When considering Quechua textile culture, Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui talks about the narrative woven into them, seemingly abstract to the eyes of the uninitiated, as dynamic forms of cosmovision redistribution. In her fabrics, Ana Hupe proposes a form of sharing enabled by a form-device distinct from books or written language.

The printed fabrics can also teach us about German ethnographic practices; they are an ethnographer’s ethnography of sorts. In the late 19th century, travelers from the recently unified Germany were responsible for establishing the first contact between Europeans and South American peoples dwelling in areas of difficult access. While they gathered objects as evidence for the existence of those cultures – and so they, themselves, could gain prestige -, they provoked transformations within those groups as they were introduced to European culture. Furthermore, 1884 was the year of the Berlin Conference, which regulated the colonization of the African territory, known as the “Scramble for Africa”, and inaugurated a new phase of European Imperialism. A few years later, 1897 saw one of history’s best-known plundering of artworks: the punitive British expedition to Benin, Nigeria, when over 4.000 artifacts were looted from the royal palace of Oba Ovonramwen Ngobaisi, among them the famous Benin Bronzes, created in the 14th century by artists from the Edo people. Official records state that 1.027 went to British museums while 1.118 were purchased by German collections. Calls for their restitution were made and continue to this day. In December of 2022, Germany returned twenty-two works of art in its possession to Nigeria, leaving empty exhibits in some museums or displaying copies in their places. The French state repatriated twenty-six bronzes in 2021, after a report published by researchers Felwine Sarr and Bénédicte Savoy. When referring to recent restitutions, Savoy speaks of a “boomerang return” – a movement that, after years of denials and absent mindedness, returns with exponential force: “restitution, decolonization, social justice, and patrimonial justice go hand in hand.” (SAVOY, 2023).

Statues never die, contrary to what Alain Resnais, Chris Marker, and Ghislain Cloquet believed in the 1953 film-essay Statues Also Die. Ariella Aïsha Azoulay talks about how these objects, so thoroughly guarded and documented in European museums, are just slumbering as they wait to be returned to their territory. They are not mere ethnographic artifacts – a reductionist approach to which they were submitted by the coloniality of knowledge -, but beings endowed with community and spiritual mediation in their place of origin. The museum-institution, heir to modern colonial thinking, severs the ties between objects and the context of their production. Also in 1953, the German Theodor Adorno decreed their downfall, as they enclose objects that possess no vital ties to their observer. Ethnographic museums still present culture as patrimony seen through an objective lens. By removing an object from and location and transferring it to another, placing it inside a glass case, the museum institutionalizes the cultural “other” and lays down separations, categories, and chronologies. In that sense, the poetics of restitution Ana Hupe operates presents the captured objects as living things, inseparable from their context, so the museum could not be their final destination, but a stop along the way, a passing place for this speaking object.

Juliana Gontijo – curator

PS.: As I encountered the works that make up this show, I listened to Ana’s many stories about encounters and separations, and what drove her to think of them as art. I’ll now tell one of these stories: in one of her trips to Benin, Ana Hupe was waiting for the confirmation of a visit to a descendant of queen Tassi Hangbé, the Kingdom of Dahomey’s first Amazon warrior. Upon being summoned by the queen, she found herself wearing jeans and had to stop in a shop and purchase a fabric (pagne) to wrap herself in. She found one patterned with throne drawings, a choice the queen approved of. It was then that she stumbled across the idea of transforming some of the looted objects into drawn fabrics.

References

BUCK-MORSS, Susan. Hegel and Haiti. Critical Inquiry, Vol. 26, No. 4.

(Summer, 2000), pp. 821-865.

HARTMAN, S. Vênus em dois atos. Revista Eco-Pós, [S. l.], v. 23, n. 3,

p. 12–33, 2020. DOI: 10.29146/eco-pos.v23i3.27640. Available in: https://revistaecopos.eco.ufrj.br/eco_pos/article/view/27640

MIGNOLO, Walter. O lado mais obscuro do Renascimento. Em: universitas humanística [online]. 2009, n.67, pp.165-203. ISSN 0120-4807. Available in: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?pid=S0120-48072009000100009&script=sci_abstract&tlng=pt.

QUIJANO, Aníbal. (2005). Colonialidad y modernidad-racionalidad.

In: Perú Indígena, vol. 13, no. 29, Lima, 1992.

SANDOVAL, Lorenzo. Weaving Waves. A platform on text, textile and technology.

In: Siegfried Zielinski and Daniel Irrgang (coords.). Node «Materiology and Variantology: invitation to dialogue». Artnodes, no. 34, UOC, 2024.

Available in: https://doi.org/10.7238/artnodes.v0i34.426915.

SAVOY, Bénédicte. O Retorno do Bumerangue. [Interview with] Márcio Seligmann-Silva. Revista Select, 13/03/2023.

Available in: https://select.art.br/o-retorno-do-bumerangue/

Un-Documented: Unlearning Imperial Plunder. Filme de Ariella Aïsha Azoulay.

35 min. 2019. Available in: https://vimeo.com/490778435.