| Ìgbáradì fun Ìwé kíkà (Challenges for the reading), 2020-2021 |

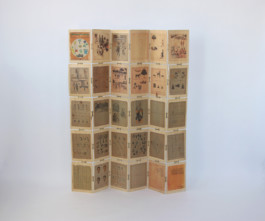

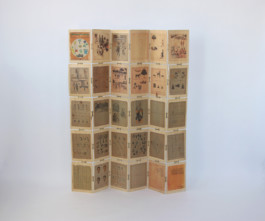

Ìgbáradì fun Ìwé kíkà (Challenges for the reading), 2020 - 2021

126 x 149 cm, 30 wood panels, metal hinges.

We went to the palace of the King of Ejigbo, the Elejigbo. The festival of Ogyian was taking place that week of September. Every afternoon before musicians began their procession from the palace, we would talk with the king of Ogyian, Oba Omowonuola Oyeyode II, who back in 2019 had been the political authority of Ejigbo for 46 years—as well, as being the most important spiritual representation of Ogyian in the world. When we spoke about Brazil, he described a trip to Salvador in 1973. He still remembered a sensation: moqueca*. Digging into other avenues for our conversation, Moisés proudly told him about the poster with the poetry of slogans I found in a bookshop around the palace. I gleefully unrolled what almost looked like archaeological find and the king was truly amazed. I read the sentences attributed to each state and commented, while Moisés looked at me sideways, indicating that I should give it to the king as a present. Of course, I had already noticed his wish for the object there on the table and knew what an honor it would be to please Elejigbo, the real, official Elejigbo, whose name I only think of in song*. However, everything about that day and the king was made manifest in the poster, he would stride beside me wherever I went, carrying the festival of Ogyian, the stationer, our favourite restaurant, the many "snaps"* people at the market asked to take of us.

I would offer him almost everything, but not the poster. We went onto other subjects, I asked about Yemọja and he told me about the women who to this day take part bare-breasted in processions in the city of Shaki that sparked my curiosity. And when it was time to go, I rolled up the poster into a tube and put it in my backpack, vertically, tightly secured between camera, notebook, wallet, another camera, films. We got on our okadas* at the door of the palace and went home.

Back in my room, I unpacked everything and went to look in wonder at the poster once again. Where was it? I looked everywhere, under the bed, in the bathroom, took everything out of my backpack, but it was gone! It was 80cm tall, rolled up, not easy to vanish. Whether called or not, god is present. The disappearance, the invisible. We need to be alive to our vital energies’ moments of exchange and renewal, so we can keep on walking with the living spring within us.

...

In the same tiny bookshop-stationer’s, I asked the man sitting by the door if he had a book to teach myself Yoruba. To start a conversation and to see if I would enter further into that world. He said no, but went to check, rummaging through his stock while Efunwale and I chatted about other things and watched a child playing, perhaps the man’s grandson.

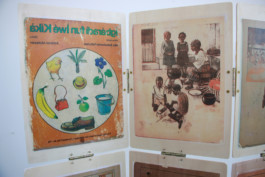

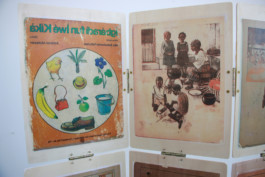

He came back with a book from the University of Ibadan from 1980, a Yoruba textbook for children. It was so old that he refused to charge me and gave it to me as a present. He could barely suspect my attachment for the yellowing pages of that beautiful book, all printed in black and white with orange … on the pages thin like newspaper paper. Very curious because it taught a language without using a single word. Pictures, exercises in imagination that had to be activated to work. It teaches us that before reading words, we should learn to read the world.

The book was, as its title made clear, a real challenge to read, the pages jumped and leapt, detaching themselves from the staples. And celebrating the mystery between the lines.

I imagine the written word challenges many traditional cultures to the present day; it isn’t by accident that a book teaching Yoruba would stimulate the imagination and spoken dialogue more than writing.

I spoke to someone I know from Benin about my experience with this book. He is twenty four and told me that when he was a child, it was forbidden to speak Yoruba in school, all the children who spoke ethnic languages were punished. I feel that recently traditional cultures are more valued and the reality in schools today might be slightly different. Although Christianity and Islam, religions defined by doctrine and a book, dominate Nigeria today, traditional cultures meddle in the system without giving up an invisible ontology that grows with the continuous ancestral celebrations.

__

* Moqueca is a typical dish from Bahia, made with fish cooked in palm oil (epo pupa in Yoruba) with onion, paprika, a lot of coriander, coconut oil, accompanied with rice, chilly and farofa, mandioc flour prepared in palm oil.

* The journey coincided with the release of the album Obatalá - uma homenagem à mãe Carmem (Obatalá – a homage to Mãe Carmem, 2019), an initiative by Grupo Ofá. Mãe Carmem is the iyálorìṣa of the Gantois terreiro in Salvador. She is the second daughter of Mãe Menininha, was consecrated to Oxaguiã and there are many songs on the album dedicated to the orisa that I remembered when I heard Yoruba words like Elejigbo.

* A snap is a selfie or portrait made quickly with the mobile phone. Because being white or Oyibo and foreigners, a lot of people would stop us and ask for a snap in the streets.

* motorcycle taxi

| Ìgbáradì fun Ìwé kíkà (Challenges for the reading), 2020-2021 |

Ìgbáradì fun Ìwé kíkà (Challenges for the reading), 2020 - 2021

126 x 149 cm, 30 wood panels, metal hinges.

We went to the palace of the King of Ejigbo, the Elejigbo. The festival of Ogyian was taking place that week of September. Every afternoon before musicians began their procession from the palace, we would talk with the king of Ogyian, Oba Omowonuola Oyeyode II, who back in 2019 had been the political authority of Ejigbo for 46 years—as well, as being the most important spiritual representation of Ogyian in the world. When we spoke about Brazil, he described a trip to Salvador in 1973. He still remembered a sensation: moqueca*. Digging into other avenues for our conversation, Moisés proudly told him about the poster with the poetry of slogans I found in a bookshop around the palace. I gleefully unrolled what almost looked like archaeological find and the king was truly amazed. I read the sentences attributed to each state and commented, while Moisés looked at me sideways, indicating that I should give it to the king as a present. Of course, I had already noticed his wish for the object there on the table and knew what an honor it would be to please Elejigbo, the real, official Elejigbo, whose name I only think of in song*. However, everything about that day and the king was made manifest in the poster, he would stride beside me wherever I went, carrying the festival of Ogyian, the stationer, our favourite restaurant, the many "snaps"* people at the market asked to take of us.

I would offer him almost everything, but not the poster. We went onto other subjects, I asked about Yemọja and he told me about the women who to this day take part bare-breasted in processions in the city of Shaki that sparked my curiosity. And when it was time to go, I rolled up the poster into a tube and put it in my backpack, vertically, tightly secured between camera, notebook, wallet, another camera, films. We got on our okadas* at the door of the palace and went home.

Back in my room, I unpacked everything and went to look in wonder at the poster once again. Where was it? I looked everywhere, under the bed, in the bathroom, took everything out of my backpack, but it was gone! It was 80cm tall, rolled up, not easy to vanish. Whether called or not, god is present. The disappearance, the invisible. We need to be alive to our vital energies’ moments of exchange and renewal, so we can keep on walking with the living spring within us.

...

In the same tiny bookshop-stationer’s, I asked the man sitting by the door if he had a book to teach myself Yoruba. To start a conversation and to see if I would enter further into that world. He said no, but went to check, rummaging through his stock while Efunwale and I chatted about other things and watched a child playing, perhaps the man’s grandson.

He came back with a book from the University of Ibadan from 1980, a Yoruba textbook for children. It was so old that he refused to charge me and gave it to me as a present. He could barely suspect my attachment for the yellowing pages of that beautiful book, all printed in black and white with orange … on the pages thin like newspaper paper. Very curious because it taught a language without using a single word. Pictures, exercises in imagination that had to be activated to work. It teaches us that before reading words, we should learn to read the world.

The book was, as its title made clear, a real challenge to read, the pages jumped and leapt, detaching themselves from the staples. And celebrating the mystery between the lines.

I imagine the written word challenges many traditional cultures to the present day; it isn’t by accident that a book teaching Yoruba would stimulate the imagination and spoken dialogue more than writing.

I spoke to someone I know from Benin about my experience with this book. He is twenty four and told me that when he was a child, it was forbidden to speak Yoruba in school, all the children who spoke ethnic languages were punished. I feel that recently traditional cultures are more valued and the reality in schools today might be slightly different. Although Christianity and Islam, religions defined by doctrine and a book, dominate Nigeria today, traditional cultures meddle in the system without giving up an invisible ontology that grows with the continuous ancestral celebrations.

__

* Moqueca is a typical dish from Bahia, made with fish cooked in palm oil (epo pupa in Yoruba) with onion, paprika, a lot of coriander, coconut oil, accompanied with rice, chilly and farofa, mandioc flour prepared in palm oil.

* The journey coincided with the release of the album Obatalá - uma homenagem à mãe Carmem (Obatalá – a homage to Mãe Carmem, 2019), an initiative by Grupo Ofá. Mãe Carmem is the iyálorìṣa of the Gantois terreiro in Salvador. She is the second daughter of Mãe Menininha, was consecrated to Oxaguiã and there are many songs on the album dedicated to the orisa that I remembered when I heard Yoruba words like Elejigbo.

* A snap is a selfie or portrait made quickly with the mobile phone. Because being white or Oyibo and foreigners, a lot of people would stop us and ask for a snap in the streets.

* motorcycle taxi